The 8th of March is celebrated around the world as International Women’s Day – a wonderful opportunity to introduce you to a selection of women artists I find inspiring. These impressive women were painters, sculptors, photographers and performers. Each of them succeeded in building a bright and unique career for themselves, despite challenging circumstances.

1. Judith Leyster (1609-1660)

Judith Leyster is one of the rare women artists from the Dutch Golden Age. Born in the city of Haarlem in 1609, her work first got noticed when she was only 19 years old. In this Self-portrait from around 1630, Judith Leyster represents herself at work. The young woman turns towards us in a rapid movement, as if we had caught her off-guard, holding her painter’s palette and her seventeen or so paintbrushes.

Her elegant dress, with its fancy lace sleeves & collar, however, point rather to Judith Leyster’s pride at being an successful artist. In 1633 she had integrated the prestigious Guild of Saint-Luke – an absolute prerequisite for any aspiring professional painter and studio owner at that time.

Due to her loose brushwork, Judith Leyster was often compared to Frans Hals. There was definitely some rivalry between the two, as records tell us that Leyster sued Hals in 1635 for “poaching” one of her apprentices, eventually receiving monetary damages.

For centuries, Judith Leyster’s work was wrongly attributed to Frans Hals, or to her husband Jan Miense Molenaer, whom she married in 1636 before slowing down her production. Happily, when The Merry Company was acquired by the Louvre in 1894, the painting was finally credited to its rightful author. Her signature was definitely unique, since she used the monogram “JL⭐️”, since “Leyster” translates as “lodestar” in Dutch.

2. Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

As a major artist of the realist movement, Rosa Bonheur was the first woman painter to receive international recognition. She was born in Bordeaux, and her father spotted her talent as a child. He notably stated that she would quickly surpass famous female portraitist Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun. In 1841, aged 19, she exhibited her first artwork at the Salon. She subsequently went on to win several medals, as well as a first public commission in 1848 for an agricultural painting: Ploughing in Nevers.

Rosa Bonheur immediately specialised in animal painting. In order to ride horse and attend livestock markets without being harassed, Bonheur, who already had short hair, got a special authorisation to wear trousers. In 1853, her painting The Horse Market brought her international fame.

Rosa Bonheur wanted to live an emancipated life, and thus, never married. In 1860, she settled in By, where she had a large workshop built, as well as enclosures for her animals – including horses, yaks and even lions, which of course modelled for her paintings. Her work demonstrates her keen sense of observation as well as unparalleled talent to make the creatures she was painting seem alive.

In 1865, she was also the first woman artist to receive the Légion d’Honneur (Legion of Honor) from empress Eugénie who is said to have declared “Genius has no gender”.

3. Berthe Morisot (1841-1894)

Berthe Morisot’s grandfather was painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. A founding member of the impressionist movement, she was the only woman among the 29 artists who took part in the group’s first exhibition in 1874. She also sold more artworks during her lifetime than Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir or Alfred Sisley.

Berthe Morisot also happens to be the woman that appears most frequently in Edouard Manet’s paintings. The two had a close friendship, and she married his brother, Eugène Manet, who was also a painter. Berthe Morisot’s husband was extremely supportive of her career, which was neither interrupted by their marriage nor by the birth of their daughter Julie in 1878. Moreover, Berthe Morisot always signed her work using her maiden name.

Although she was initially influenced by Edouard Manet’s dark palette at the beginning of the 1870s, Berthe Morisot quickly developed her own style. She retained the light colours used by her master Camille Corot, as well as his taste for painting outdoors. Although her subject matter remains quite conventional, Morisot’s art epitomises the spontaneous, gestural brushstrokes so often associated with impressionism. From this point of view, she is certainly the most radical of the impressionists, with her ‘sketch’-like style and audacious compositions, which often combine the intimate, domestic space with the public space.

In 1891, Berthe Morisot wrote: « I do not believe there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, and yet that is all I would have asked for, because I know that I am worth it ».

4. Camille Claudel (1864-1943)

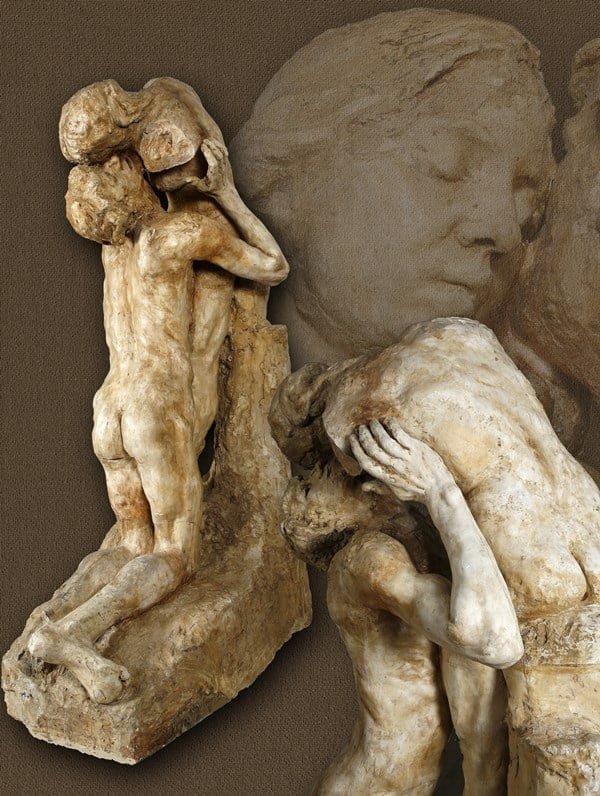

As a child, Camille Claudel would create sculptures from blocks of clay she would pick up in the countryside. While her mother opposed her passion, she was supported by her father and by sculptor Alfred Boucher, who noticed her talent.

In 1882, Camille Claudel started renting a studio with other young sculpturesses. Their teacher, Alfred Boucher, was soon replaced by Auguste Rodin. He was immediately seduced by the young woman’s talent and spirit. Two years later, she integrated his group of practitioners and collaborated with Rodin on many projects – she is notably said to have been in charge of sculpting the hands from the famous Burghers of Calais.

A fiery romance devoured the two sculptors until 1892, mutually feeding their work, although Claudel was keen to break away from Rodin’s influence. In 1888, she was granted an honorable mention at the French Artists’ Salon for a plaster group named Sakountala, after a story written by Indian poet Kālidāsa. The sculpture shows a husband and wife reunited after years of separation due to a magic spell. The piece could be considered as a pendant to Rodin’s famous Kiss. The man is kneeling before the woman here, and both nudes are rendered with great freedom. Claudel’s talent is particularly evident in the figures trepidating flesh, as if they were anticipating their imminent physical contact.

Sadly, Camille Claudel became more and more isolated as she suffered bouts of paranoia. In 1912, she destroyed her sculptures. The following year, her family had her admitted to a psychiatric institution where she stayed until her death in 1943. She never sculpted again. Her work was slowly rediscovered from the 1950s onwards. Since 2017, a whole museum is devoted to her work in Nogent-sur-Seine. A long-deserved homage to this talented sculptress of which Rodin himself once said: “I showed her where she might find gold, but the gold she finds is definitely her own.”

5. Florence Henri (1893 1982)

Talented photographer Florence Henri mirrored all the avant-gardes movements from the beginning of the 20th century. Born in the United States to a French father and a German mother, she went to live in Rome after the untimely death of both her parents. There she met artists connected futurism. She then left for Berlin, aged 20, where she met the likes of Vassily Kandinsky, whilst her partner, art historian Carl Einstein, introduced her to cubist painting.

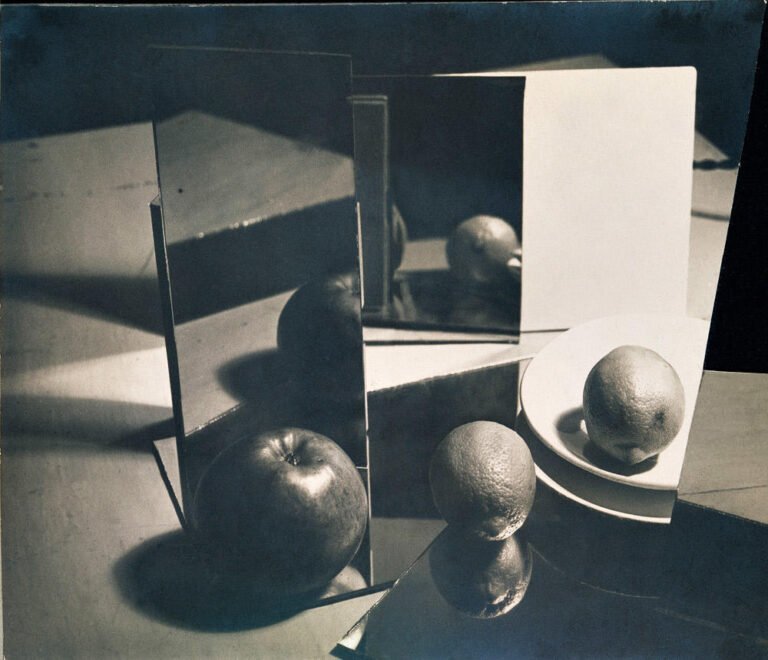

In 1924, Florence Henri moved to Paris. She studied with André Lhote and Fernand Léger while frequenting painters such as Sonia Delaunay – another artist who could have been included in this selection! – or Piet Mondrian. But in 1927, Florence Henri discovered photography during a summer course at the legendary Bauhaus.

Florence Henri’s photographs integrate her pictorial experiments with cubism and constructivism. In her Self-portrait from 1928, she arranged metallic balls in front of a mirror so as to replicate the impression of space, as well as the lines and geometric shapes.

Florence Henri also enjoyed cutting her photographs of still-lives to make collages that she would photograph again to obtain a unified surface, thus creating a perfect photographic equivalent to cubist paintings. Finally, the artist created many female nudes, even supplying pictures to erotic journals. This was a meaningful way for a woman to reclaim power on a photographic genre which had long been the prerogative of men.

6. Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

Frida Kahlo is the most famous artist on this list. In a way though, she become an artist “by accident”. From childhood, Frida Kahlo dealt with some serious health issues. Aged 6, she suffered from poliomyelitis, which impaired her walking. She dreamed of becoming a doctor, but abandoned this vocation in 1925, after a serious bus accident left her with numerous fractures. This is when she began to paint, in her hospital bed, using a mirror fixed to the ceiling. « My painting carries with it the message of pain » said the artists who underwent a total of 35 surgeries in her life… while producing 150 paintings.

In 1928, she met Diego Rivera, a brillant muralist who encouraged Frida Kahlo to keep painting. Their stormy relationship was marked by Rivera’s countless infidelities, which profoundly wounded the young woman, while also pushed her to become even more emancipated. Frida Kahlo was deeply committed to women’s rights and was openly bisexual and allegedly had affairs with the likes of Leon Trotsky and Joséphine Baker.

Frida Kahlo was very proud of her heritage, and merged modern European painting styles with Mexican popular culture. Although André Breton, whom she met in 1938, was keen to associate her with surrealism, Frida Kahlo refused to let her art be “labelled”. Many of the 55 self-portraits she produced over the course of her career depict her with sophisticated floral hairstyles, on a luscious vegetation backdrop, surrounded by animals such as monkeys and parrots, in a style that is uniquely her own.

7. Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975)

Barbara Hepworth is doubtless one of the greatest sculptors of her generation – she did not wish to be referred to as a “sculptress”. Fascinated as she was by the shapes we encountered in nature, this Yorkshire-born English artist created nearly 600 sculptures between 1925 and 1975, the year of her death.

As a student of the Royal College of Art in the 1920s, she and her friend Henry Moore started no longer using preparatory models, instead working full-scale directly. Barbara Hepworth mainly worked with stone, wood and bronze. When she used plaster, it was applied in thick layers over an aluminium armature, then « carved » like a block of marble.

In the 1930s, Barbara Hepworth abandoned all references to reality and devoted herself to abstraction. She was encouraged by her exchanges with artists like Georges Braque or Piet Mondrian. She explored the solid and the void, in an attempt to translate her physical sensations with regard to the landscape, particularly that of St Ives in Cornwall, where she settled with her family in 1939. For instance, her famous sculpture Pelagos evokes the rolling of waves, while its strings symbolised, « the tension I felt between myself and the sea, the wind or the hills ».

Barbara Hepworth’s personal life was not simple since she had two husbands and four children, including triplets, not to mention war-related disruptions. But she never stopped working. The last decade of her career was particularly prolific. In 1968, she declared : « while always remaining constant to my conviction about truth to material, I have found a greater freedom for myself. »

8. Niki de Saint-Phalle (1930-2002)

Catherine Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint-Phalle was nicknamed « Niki » by her American mother as a small child. She was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine in France, and grew up in the United States. She started making drawings with curved lines from age 6. Niki de Saint-Phalle started her career as a model for magazines such as Vogue, Life Magazine or Elle, between the ages of 17 and 25.

As a self-taught artist, she became close to the French Nouveaux Réalistes (New Realists) in 1960, thanks to Daniel Spoerri and Jean Tinguely, who would become her second husband. But on 12 February 1961, art critic Pierre Restany attended the first of Niki de Saint-Phalle’s Tirs (Shots) and was so enthralled that he asked her to officially join the group. Her approach was indeed extremely innovating: she filmed herself with a rifle, shooting at paint-filled bags, which had previously been attached to a vertical surface and covered in plaster. Situated at the crossroads between painting, sculpture and performance, her creative process was fuelled by destruction.

Niki de Saint-Phalle had a committed feminist stance. She once declared: « I understood from an early age that men had the power, and I wanted this power. Yes, I would steal their fire. I would not accept the limits that my mother tried to impose on my life because I was a woman. » In 1964, she started making her Nanas (Chicks): monumental sculptures made from papier mâché or polystyrene depicting large, imposing and opulent women, perhaps embodying the matriarchal society the artist was longing for.

Finally, in 1979, she started working on her comprehensive, all-embracing work of art: her Tarot Garden in Capalbio, Tuscany – a garden inhabited by giant sculptures covered in glass and ceramic mosaics, inspired by the 22 major arcana of tarot cards. It opened to the public in 1998. For 13 years, and quite symbolically,, Niki de Saint-Phalle resided inside her sculpture of the Empress.

9. Ana Mendieta (1948-1985)

Ana Mendieta was born in Cuba in 1948 and was one of the many children sent to the United States in 1961 after the revolution, as part of the Peter Pan operation. She studied fine arts at the University of Iowa, with a focus on Intermedia. Her work is at the crossroads between photography, video, Land Art and performance, and is profoundly unique.

Her Silueta series, which she developed between 1973 and 1980, is particularly fascinating. The artist confronts a stylised representation of a female body with the elements of nature. For instance, inspied by the rituals of Santería, a syncretic Cuban faith merging African and Catholic practices, religion cubaine, Ana Mendieta sets one of these Siluetas on fire and films it lighting up the night sky of Oaxaca, Mexico, before slowly disappearing. This figure perhaps evokes a mother-goddess or a tree of life.

In her Super 8 film Creek from 1974, Ana Mendieta is directly (and literally!) at one with the elements – water in this instance. In this video with no clear beginning nor end, and no narrative structure, the viewer watches the artist’s body, lying naked in Oaxaca’s San Felipe Creek. The scene is powerful, peaceful and vulnerable in equal measure, a little like the status of women. Ana Mendieta explores her relationship with mother-earth and, perhaps, the sacred feminine.

Ana Mendieta’s career was cut short by her brutal death in 1985, after falling from the window of the New York apartment she shared with her husband, the minimalist artist Carl Andre. The unclear circumstances of her death (although Andre was acquitted) made her into a symbol for feminists’ fight against domestic violence.

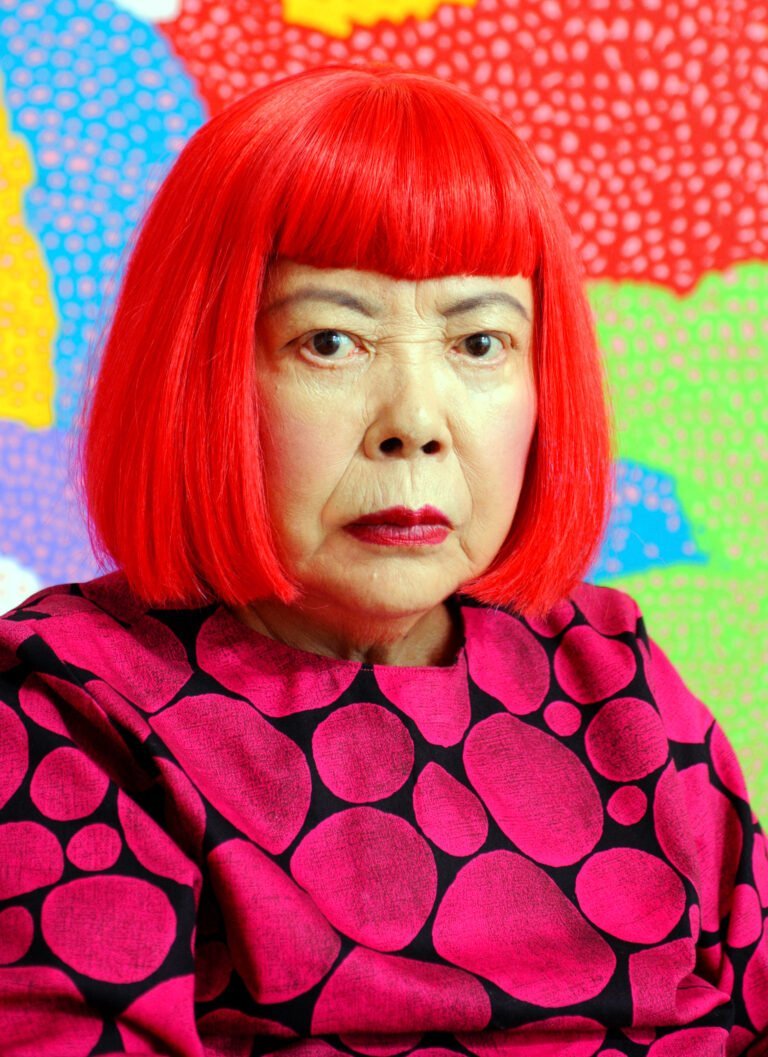

10. Yayoi Kusama (1929-)

Yayoi Kusama is the best-selling female contemporary artist in the world. She began drawing as a child – but her circumstances were far idyllic. The Japanese artist recounts having the sensation of disappearing in her parents’ flower fields. Meanwhile her mother, who was unsupportive of her daughter’s artistic endeavours, regularly destroyed her work or confiscated her supplies. She would also ask the young Yayoi to spy on her father, and she effectively caught him several times committing adultery. Thus, flowers and phalli are recurring in Yayoi Kusama’s work, as are polka dots.

When she left Japan to live in New York in 1958, she had a hard time as a female Japanese artist in the very masculine-driven art world. She nevertheless managed to exhibit her work and became increasingly popular in the 1960s through her performances and environments.

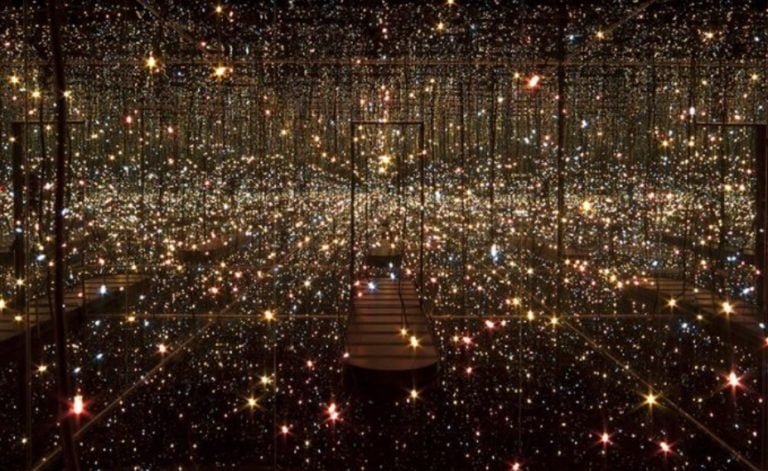

Working from the visual hallucinations she experienced from childhood, especially of the polka dots escaping from a patterned tablecloth and invading the space around it, Yayoi Kusama created environments – spaces that unlike installations, surround the viewer. I have a very vivid memory of my first encounter with Kusama’s work when I was a teenager. It was a piece called Fireflies: a room covered in mirrors and small lights, water on the floor, infinitely reproducing a dream-like space.

Similarly, Yayoi Kusama, who has been living in a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo since 1977 (at her own request), works in her studio every day, repeating the patterns that epitomise her anxieties ad infinitum. Her art has a deeply therapeutic goal.