Motherhood is one of those universal subjects in the art of all civilizations around the world. It has inspired an astonishing amount of works. Whether these representations are real or abstract, they all give us insight as to the place held by women and mothers in society, as part of a lineage or more simply as an important family member.

Let’s look at some examples of works, from the Antiquity to the present day, which showcase mothers, mother-artists, or pay a more universal homage to motherhood. I noticed subsequently – whether or not this is a coincidence – that my selection highlights several female artists!

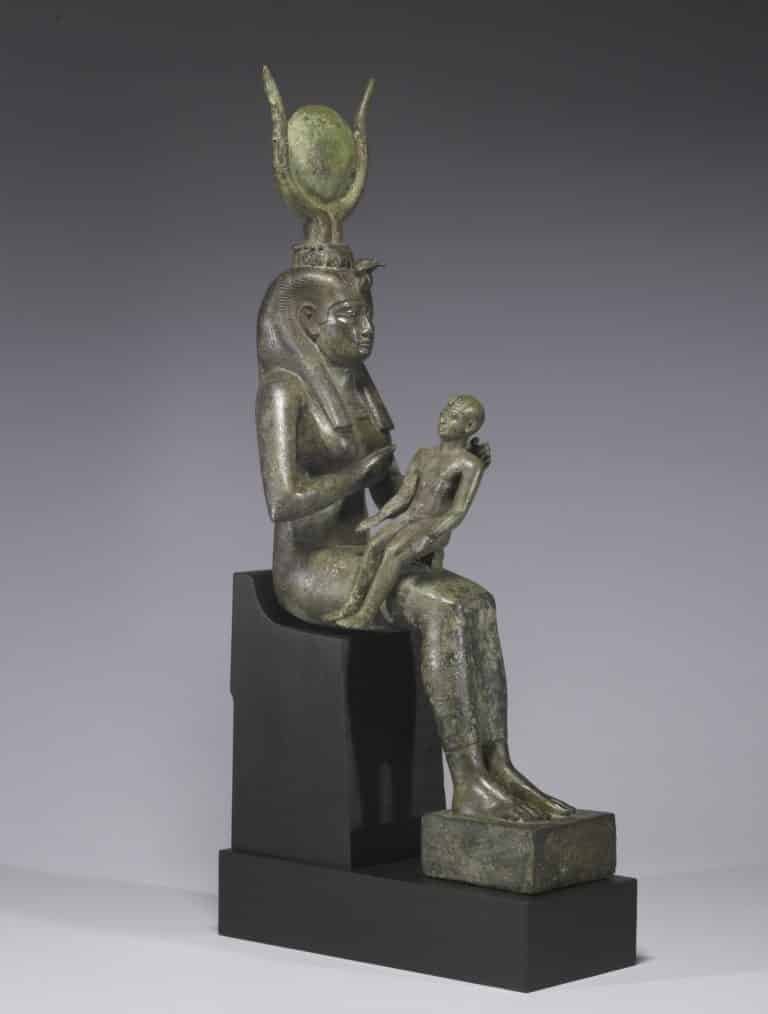

1. Isis with the Child Horus, Late Period (ca. 680-640 BC)

Among the many ancient representations of motherhood, the goddess Isis is one of the most fascinating figures. In the ancient Egyptian belief system, Isis embodied the feminine ideal and a role-model for all queens. Although she is known as the loyal wife of God Osiris, she was first and foremost a powerful magician. According to Egyptian mythology, Isis managed to find and assemble the pieces of Osiris’ body after he had been dismembered by his brother Seth, who was jealous of his power. Once she had brought her husband back to (a form of) life, she conceived a child: Horus, who later became associated Egypt’s Pharaohs in the world of the living.

This bronze statuette shows the goddess with her son Horus on her lap. Isis touches her breast, indicating that she may be about to nurse him. But the rigid attitude of both characters, placed perpendicular to one another, suggests that the object’s purpose is more symbolic than realistic. In the first millennium BC, Isis was widely venerated in her own right, throughout the Mediterranean. The vulture on her forehead, as well as her headdress, which consists of a solar disk flanked by cow horns (usually associated with the goddess Hathor) indicates Isis’ powerful role as universal mother-goddess.

2. Sandro Botticelli, The Madonna and Child with the young Saint John the Baptist (ca. 1470-1475)

Fast forward a few centuries in the history of art, and the role of supreme mother was definitely taken up by the Virgin Mary, as demonstrated by the countless representations of the Madonna & Child, from the Roman times and especially from the end of the 12th century.

But although if this abundant imagery may seem repetitive, it is fascinating to compare artists’ various interpretations of the same subject. Each one tells us about the times it was produced in, and not merely with regard to religious practices. This example is one of my favorite paintings in the Louvre. The master of the Quattrocento, Sandro Botticelli, was celebrated for the grace and delicacy of his figures. But looking beyond his elegant and graphic style, his interpretation of the Madonna and Child reflects the thoughts and ideas of the Florentine Renaissance.

The scene takes place in an enclosed garden, surrounded by roses, which are symbols of virginity. But although Catholic doctrine tends to downplay the physical bond between Mary and her child, their intimacy is evident here. The tenderness of the gestures, Jesus’ baby face and the discretion of the halos emphasise their humanity much more than their divinity. Revised in the light of Renaissance humanism, Mary becomes even more universal, since she invokes the viewer’s own, personal experience of maternal love.

4. Hyacinthe Rigaud, The Léonard Family (1692)

When it comes real, contemporary families, however, art historical depictions seldom left room for open displays of tenderness, which would have interfered with the overall seriousness associated with this type of imagery. The Léonard Family is one of the few family portraits produced by the painter Hyacinthe Rigaud, who remains famous for his notorious portrait of The Sun King, Louis XIV.

Parisian printer Pierre Frédéric Léonard (1665-1725) and his wife Marie-Anne des Essarts (1670-1706) belonged to the upper bourgeoisie. Rigaud painted them with their daughter Marie-Anne, born in 1690. The landscaped background, as well as the abundance of drapery, is inspired by the portraits made by court artists such as Van Dyck or Peter Lely. In fact, these visual codes raise the Léonard’s social status to the rank of nobility.

Nevertheless, the artist does weave intimacy into this otherwise ceremonial painting. The father, in the middle, delicately strokes his wife’s shoulder, while she hands some cherries to her baby daughter. The latter, which is depicted with an unusual amount of care, temporarily interrupts her play with the little dog to grab the fruit. The tight framing of the work, as well as the exchange of glances underlines the harmony within the family, while respecting the necessary decorum for this type of portrait.

3. Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun, Madame Vigée le Brun and her daughter Jeanne-Lucie, known as Julie (1786)

Depictions of motherly love became more common in the 18th century. At the 1787 Salon, Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun exhibited a self-portrait with her daughter Julie. The obvious affection that emerges from the painting contrasted with the solemn portraits of royal or aristocratic families. Therefore critics was rapidly referred to it as Maternal Tenderness.

Even compared to The Léonard Family (above) produced barely a century earlier, the contrast is striking. The sophisticated poses give a stilted character to the work. Vigée le Brun, on the contrary, highlights the tenderness she shares with her daughter. As such, the artist was fully in tune with her times: in 1762, the Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau had published Emile or On education, which advocated close relationships between parents and their children, as well as child-rearing methods which respected children’s natural tendencies. Also, little Julie’s spontaneity is clear in this painting, as are the loving gestures of her mother.

But although the interest in childhood is undeniable, especially in the freshness of the little girl’s gaze, Vigée le Brun’s goal was also to assert herself as an accomplished woman. The artist, who has successfully made a career for herself as a painter and established himself in a very masculine environment, showcases herself here as being completely happy and fulfilled in her role as mother.

4. Berthe Morisot, Eugène Manet and his daughter in Bougival (1881)

Cette œuvre est singulière au sein de cette sélection, car elle montre un père et non une mère… et pour cause, cette dernière se trouvait derrière son chevalet ! Berthe Morisot peignit son mari Eugène Manet avec leur fille unique Julie lors d’un séjour à Bougival. Née le 14 novembre 1878, Julie Manet devint le modèle de prédilection de sa mère, et posa régulièrement pour d’autres impressionnistes, dont Auguste Renoir.

Berthe Morisot ne cessa jamais de peindre, et fut pleinement soutenue par son mari dans sa carrière artistique. C’est d’ailleurs lui qui poussa son épouse à présenter ce tableau à l’Exposition impressionniste de 1882, alors même qu’elle était réticente. L’œuvre fut très bien reçue et le critique d’art Philippe Burty la qualifia même « d’impressionnisme par excellence ».

La scène est effectivement charmante : Eugène et Julie Manet sont installés dans le jardin de la maison située au 4 rue Princesse à Bougival, que la famille loua chaque été entre 1881 et 1884. La petite fille est absorbée par son jeu de construction, dont le plateau est posé sur les genoux de son père, qui la regarde d’un air attendri. Plus touchant encore : la palette colorée de Berthe Morisot souligne visuellement l’intimité déjà sensible entre les personnages. Le chapeau et le pantalon du père sont traités avec des touches de rose et de violet qui répondent parfaitement aux teintes de la robe de la petite fille, et semblent même l’entourer.

This piece is unique in this selection, because doesn’t show a mother but a father… and with good reason, because the mother is actually on the other side of the easel! Berthe Morisot painted her husband Eugène Manet with their only daughter Julie during a stay in Bougival. Born on 14 November 1878, Julie Manet became her mother’s favourite model, and was also painted regularly by other impressionists, including Auguste Renoir.

Berthe Morisot never stopped painting, and was fully supported by her husband in her artistic endeavours. He actually pushed his wife to present this painting at the 1882 Impressionist Exhibition, despite her reluctance. The painting was very well received, with art critic Philippe Burty even referring to it as “Impressionism par excellence“.

The scene is indeed utterly charming: Eugène and Julie Manet are in the garden of a house located at no 4, rue Princesse in Bougival, which the family rented each summer between 1881 and 1884. The little girl is absorbed by her construction game, the board of which rests on her father’s lap, who gazes at his daughter tenderly. An even more touching detail is that Berthe Morisot’s colourful palette visually highlights the bond between the characters. Eugène’s hat and trousers are rendered with pink and purple brushstrokes that perfectly match and even seem to surround the pink hues on the little girl’s dress.

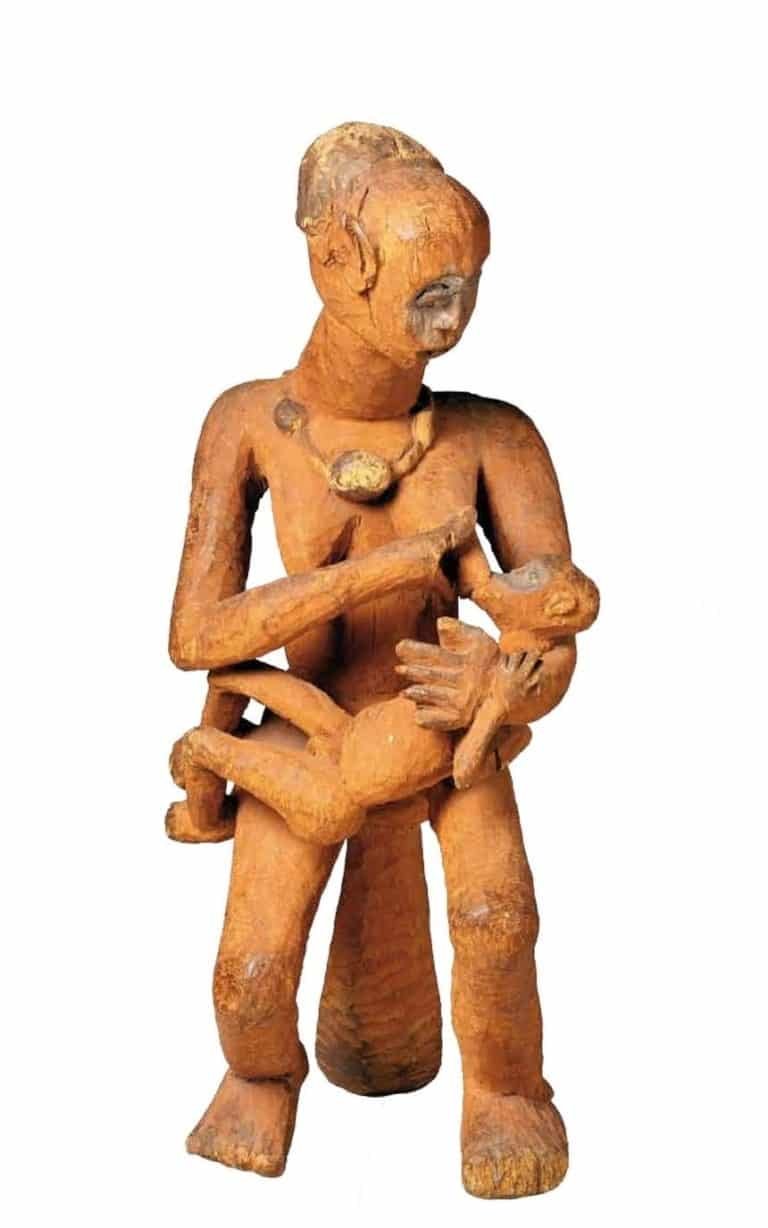

5. Kwayep, Maternity (early 20th century, before 1912)

This painted wooden sculpture shows a woman breastfeeding her baby. But unlike the sculpture of Isis and Horus, the characters are far from rigid. Although their bodies are geometrical and outstretched, their is a firm contact between the mother and her child. She holds in her arms, while gazing at him lovingly.

The blue-violet makeup on the faces, as well as the woman’s headdress, identify these characters as belonging to the royalty of the Bamileke population. In Cameroon’s Grassland, the social organisation is based on chiefdoms and imagery of mothers and children plays an important role. Indeed, the king’s rule begins at the birth of his first child.

It is likely that King Njike II commissioned this sculpture of his wife and first-born son from artist Kwayep. But this sculpture is not a mere symbol of fertility and lineage. Kwayep introduced a sense of tenderness as well as a unique dynamic style to his work. Indeed, the woman is seated on a stool, but in an unstable balance which suggests movement and imparts astonishing spontaneity to the sculpture, as the artist had taken a snapshot of the queen in mid-action.

7. Barbara Hepworth, Mère et enfant (1934)

Barbara Hepworth est une figure incontournable de la sculpture moderne britannique. Comme Henry Moore et John Skeaping, elle préconisait la taille directe, travaillant à même la pierre au lieu de passer par des maquettes ou des épreuves en plâtre. Ainsi, le rapport entre l’artiste et le matériau était sans intermédiaire et préservait toute sa vitalité.

Le sujet de la maternité découlait naturellement de cette vision, et d’autant plus à la fin des années 1920 et au début des années 1930. En effet, cette thématique se trouvait au cœur de la vie de Barbara Hepworth, qui eut un fils en 1929, puis des triplés en 1934. Cette œuvre est intéressante car c’est la première fois que l’artiste creusait un espace entre la figure de l’enfant de celle de la mère pour les rendre indépendants. Pour autant, la mère et l’enfant restent issus du même bloc de pierre d’Ancaster. Des critiques de l’époque y ont vu une matérialisation de l’expérience de fusion puis de séparation que constitue la grossesse et l’accouchement : l’enfant, issu du corps de sa mère, est pourtant un individu à part entière.

A compter de cette date, le travail de Barbara Hepworth prit une direction plus abstraite. Elle se concentra sur la pureté des matériaux, dont elle met en valeur la dimension tactile – par exemple, ici, en polissant la pierre anglaise – tout en la façonnant dans des formes organiques qui évoquent la nature et le paysage.

Barbara Hepworth is a key figure in modern British sculpture. Like Henry Moore and John Skeaping, she advocated direct carving, working on stone instead of using models and plaster casts. This unmediated relationship between the living artist and the material enabled the sculpture to keep all its vitality.

The subject of motherhood was perfectly aligned with this vision, especially in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This theme was paramount to Barbara Hepworth, who had a son in 1929, then triplets in 1934. This work is interesting because, for the first time, the artist has dug a space between the figure of the child and that of the mother to make them independent. However, the mother and the child are still carved from the same block of Ancaster stone. Critics at the time interpreted this as materialising of the experience of oneness & separation inherent to pregnancy and childbirth: the child, although born from his mother’s flesh, remains a unique individual.

From this date onwards, Barbara Hepworth’s work took a more abstract direction. She concentrated on highlighting the beauty of the materials, emphasising their tactile dimension. Here, for instance, she polished the English stone and shaped it into organic forms evoking the natural landscape.

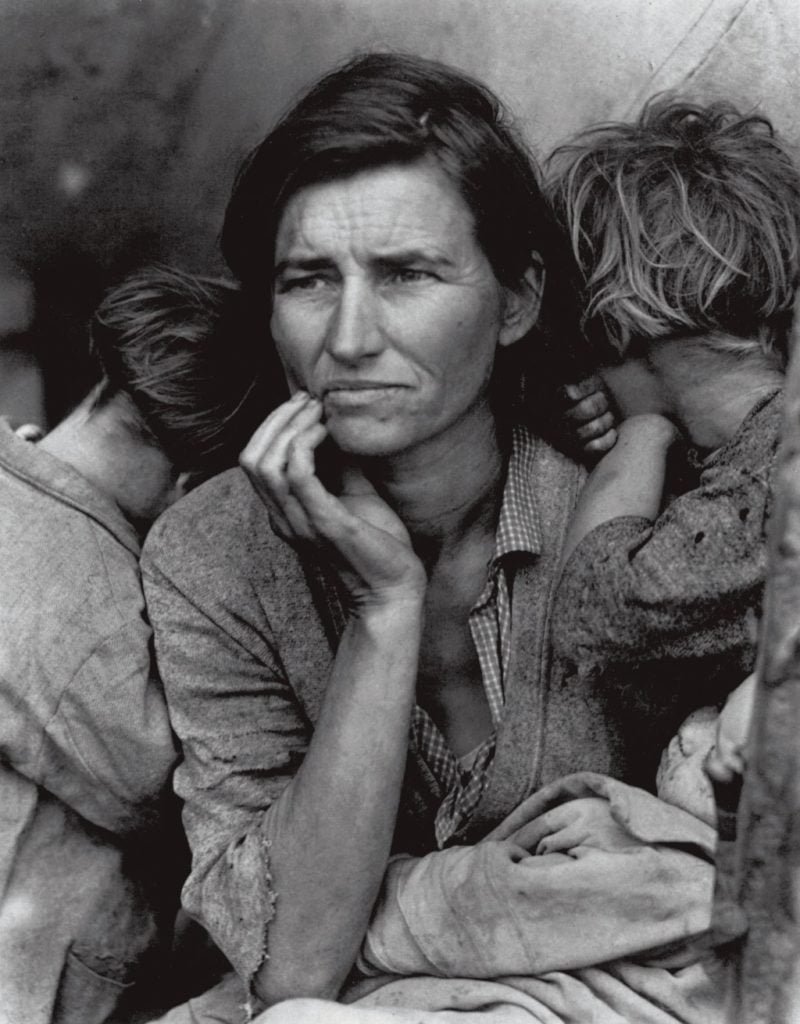

8. Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother (March 1936)

Dorothea Lange took her most famous photograph in 1936 while working for the Farm Security Administration. Lange had been asked her to document the situation of farmers affected by the Great Depression in the United States. In March 1936, on her way home after her day’s work, she was intrigued by a sign along the road which led her to a pea picker camp. There she came across a family and took a series of pictures, starting with an overview before progressing to closer shots of the mother, culminating in this legendary portrait.

The model, Florence Owens Thompson, remained anonymous until 1978. Dorothea Lange had not written down her name, although she clearly exchanged a few words with the young woman, judging from her notes: « March 1936. Migrant agricultural worker’s family. Seven hungry children. Mother aged 32. Father is native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers camp, because of the failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tent in order to buy food. Most of the 2500 people in this camp were destitute. »

This photograph is among the most famous in the history of photography, was widely printed in the press. With this courageous Cherokee mother figure, Dorothea gave a face to the Great Depression: exhausted and worried, but also strong, resilient and extremely dignified.

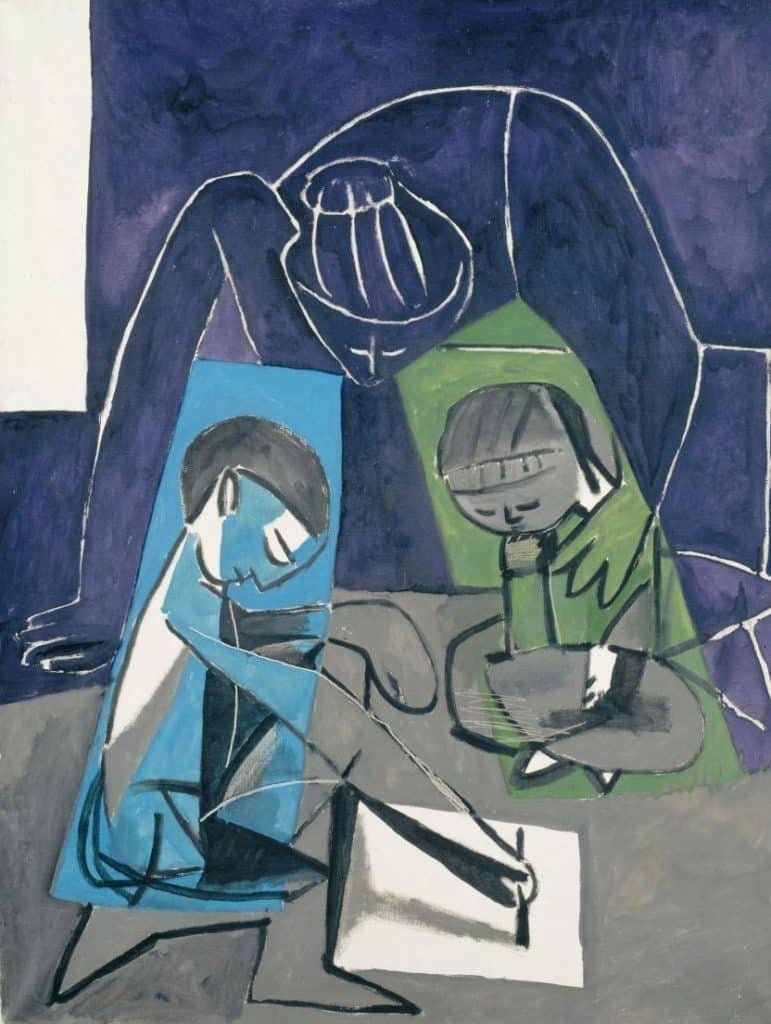

9. Pablo Picasso, Claude drawing Françoise and Paloma (17 May 1954)

Pablo Picasso painted his children Claude and Paloma in 1954 with their mother Françoise Gilot. All eyes are on the blank page that Claude is drawing on. The white paper seems to respond visually to the white area on the top left-hand corner of the painting, which probably materialises the light coming through a window.

The composition is very simple. Contemplated against the light, the characters are immersed in a luminous darkness. Furthermore, the artist uses ranges of blue and deep green to highlight his two children. Their mother, on the other hand, seems to stand out against the dark background only by a few light contours. Her silhouette, however, forms a protective and loving arch that surrounds and unites her children. The cohesion is silent yet evident between the three characters.

Picasso, on the other hand, is more a witness than a real part of this scene. Françoise Gilot actually left Picasso in 1953, and settled in Paris with the children. The artist painted this painting during one of their visits to Vallauris during the children’s half-term break. The work‘s refined, graphic style is reduced to a few essential lines, which perhaps testifies both to the void in Picasso’s world after their departure, and to their discreet but indelible presence.

10. Louise Bourgeois, Maman (1999)

You have doubtless already seen one the gigantic spiders created by Louise Bourgeois? Although these sculptures’ connection with motherhood is not obvious at first glance, their title translates as « Mummy ». The artist spoke of how her spiders are not intended to scare, despite their imposing size.

Louise Bourgeois first associated spiders with her mother in a drawing from 1947. Her mother worked at the head of a tapestry restoration workshop: “Like a spider, Bourgeois said, my mother was a weaver.” Beyond the metaphor of the art of weaving, Louise Bourgeois saw spiders as intelligent and benevolent creatures, which eliminate parasites such as mosquitoes.

The first monumental spider was created for the hall of the Tate Modern in London, out of stainless steel. The other versions, intended for the outdoors, are in bronze. The mother-spider’s gigantic legs effectively coax the view who walk under the sculpture, and perhaps spot, under her abdomen, her sack filled with twenty-six marble eggs.

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.