In this unprecedented global context, museums around the world have closed until further notice. Thankfully, digital technology has made it possible for museums to come to us. While the works of art are taking a well-deserved break from visitors who are self-isolating, why not explore a few pieces addressing interiors and interiority as their subject matter? Here are ten art historical takes on lockdown.

1. Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

An a time when family gatherings are not allowed, this double portrait shows the wedding of Giovanni Arnolfini, a wealthy banker who settled in Bruges in 1421, and his wife Giovanna Cenami. Their joint hands, placed between the chandelier and the little dog (most likely a symbol of fidelty) bring balance and unity to the composition.

In the 15th century, the sacrament of marriage did not have to be celebrated by a priest. Weddings could be held in private, as long as there were two witnesses present. We can actually see them in the reflection of the round mirror at the back of the room. Oil painting, a technique which originated in Italy, allowed Van Eyck to achieve minute precision as well as an impressive level of detail. For instance, the mirror’s frame is decorated with representations of the fourteen Stations of the Cross.

Other elements, like the costumes, the wooden furniture, the carpet on the floor, or even the presence of oranges – a luxurious imported fruit – point to the couple’s material wealth. But the spouses have removed their shoes here. While Giovanni’s discarded footwear is obvious, in the bottom left corner, Giovanna’s red shoes are placed near the sofa, at the back of the painting. We are witnessing an intimate spiritual union, and Van Eyck’s work serves as an elaborate marriage certificate.

2. Caravaggio, The Lute Player (1595-1596)

For many of us, lockdown has been an opportunity to learn (or practice) a musical instrument. In this piece created by Caravaggio during his Roman period, a young man sits before a table, on which flowers, fruit, a musical score and a violin are arranged. The lateral lighting is typical of the artist and emphasises the volume of the different parts of the painting.

But despite his dramatic light effects, Caravaggio’s main concern is naturalism. In keeping with the painter’s taste for imitating reality, ‘warts and all’, most of the objects have flaws: the pears are scratched, the paper is slightly torn and the violin even has a broken string.

The musical notes on the score actually make out a song by Jacques Arcadelt, called “You know that I love you”. This perhaps supports the theory that the model might be Mario Minniti, who was Caravaggio’s lover. According to art historian Franco Camiz, he could also be the castrato singer Pedro Montoya. Ultimately though, the sensual young man and his open shirt don’t attract our gaze any more than the fruit and flowers do. Althouth the painting as a whole functions as an invitation to the pleasures of life, Caravaggio does not seek to prioritise them. As he once said: “It requires as much work to make a good painting of flowers as one of people.”

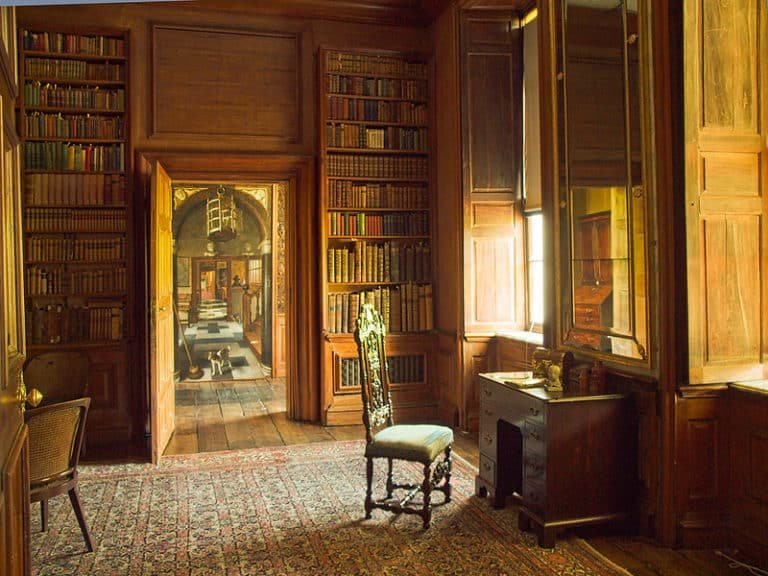

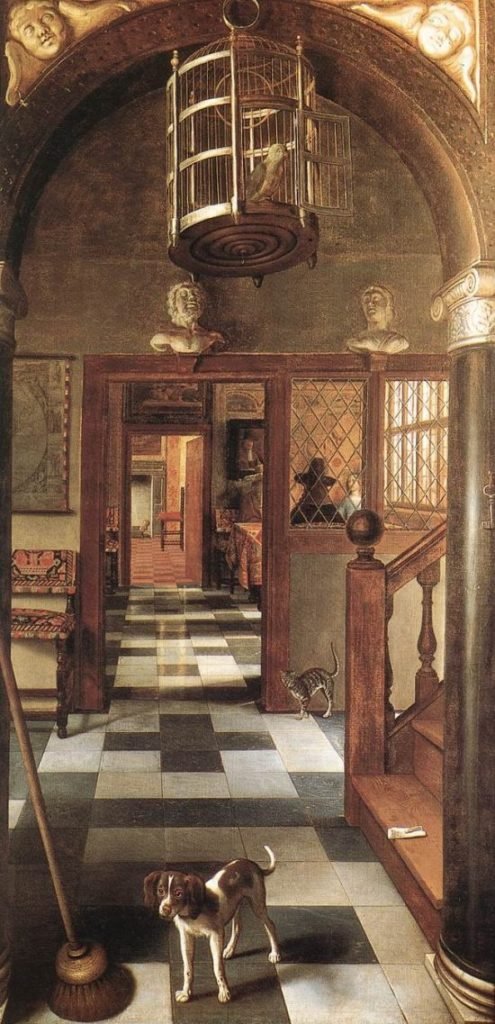

3. Samuel van Hoogstraten, View through a house (1662)

I am always impressed, not to say intimidated, by how impeccable 17th century Dutch interiors are. Their abundance in the history of painting also testifies to their symbolic attachment to domestic space: a tidy home was an outward expression of exemplary morals. So quite naturally, the broom is the first item to greet the viewer.

But our gaze is quickly drawn into the background, because Samuel van Hoogstraten, a talented disciple of Rembrandt, was a master in the art of trompe-l’oeil. In this painting, he shows us a series of successive rooms, thereby creating an illusion of depth. Today the painting hangs on the wall of a corridor at Dyrham Park, and definitely does a great job at tricking the eye.

As viewers, we can discreetly peek inside this home. Its inhabitants, who are sitting around a table in the next room, seem distracted by their conversation, although the reflection in the mirror casts some doubt. The animals, however, are not fooled: while the dog seems curious of our presence, the cat seems more suspicious. As for the parrot, perched on the edge of its open cage, it is a bit like us: on the threshold, partly closed in, but looking out.

4. Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Reader (1770)

Fragonard’s radiant Reader sits in an armchair, holding a small book in her right hand. Her yellow dress creates a strong contrast with the purple ribbons and the cushion she is lightly propped up against. The painter renders the various materials wonderfully with his textured brushstrokes. He doesn’t allow us to read the book’s text though, as we could in Caravaggio’s work. In all likelihood, she is reading a novel, a literary genre that took off in the 18th century, as did reading cabinets.

The artist’s loose and rapid brushwork gives the painting a sketchy character. This style is reminiscent of his “Fantasy figures” – a series of fifteen paintings Jean-Honoré Fragonard produced from 1769. Among these is the famous painting of a man, who, for a long time, was wrongly dentified as a portrait of Denis Diderot philosopher of the Enlightenment.

The Reader‘s extravagant clothing, its color scheme and its format all correspond to those of the Fantasy figures. But the fact the young woman is shown from the profile, immersed in her reading, instead of frontally like the others are, cast doubt as to whether it was associate to the series. But a preparatory drawing found in 2012, and the use of scientific imagery in 2017 eventually confirmed that the model’s face was initially turned towards the viewer.

5. Caspar David Friedrich, Woman at the Window (1822)

Caspar David Friedrich is renowned for his allegorical landscapes that insert human figures in the immensity of nature. But the famous German romantic painter also produced three indoor scenes, including this tiny painting. Its setting is a simple, dark room, of which the viewer only sees the walls and a piece of the wooden floor. Our gaze is inevitably drawn towards the woman at the centre of the painting.

This is Caroline, Caspar David Friedrich’s wife, whom he married four years prior. Her back is turned because she is in her husband’s studio, looking out of the window. She is most likely observing a boat sailing on the Elbe river: its mast creates a strong line in the upper half of the composition. In the distance, on the other bank, a thin row of poplars comes into view.

In a delicate harmony of blues, greens and ocher, modulated by the subtle Spring light, the painting invites us to contemplate within ourselves as well as by looking outdoors. Ultimately, it reminds us that we can always travel, without even leaving our homes.

6. John Everett Millais, Mariana (1851)

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – inspired by the art of the Middle Ages, before Raphael – was founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, three students at the Royal Academy. Their sought to renew English art, as they felt it had become overly conventional and lethargic.

Millais’ painting has a literary source. It is based on Tennyson’s poem, Mariana (1830), inspired by a play called Measure for measure, written by Shakespeare in the early 17th century. The character of Mariana, abandoned by her fiancé Angelo after the sinking of the ship transporting her dowry , yearns for her lost love. The painting was exhibited in 1851 with these few lines by Tennyson: “She only said, ‘My life is dreary, He cometh not,’ she said; She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary, I would that I were dead!“

The dead leaves scattered on the floor evoke her lengthy wait and the passing of time. They also create a visual transition between the stylised flowers and leaves on the walls & the embroidery, and the trees outside. Mariana’s body language, meanwhile, echoes the position of the needle in her craft and highlights her impatience and melancholy. The happy Annunciation scene depicted on the windows seems to taunt our nostalgic heroine.

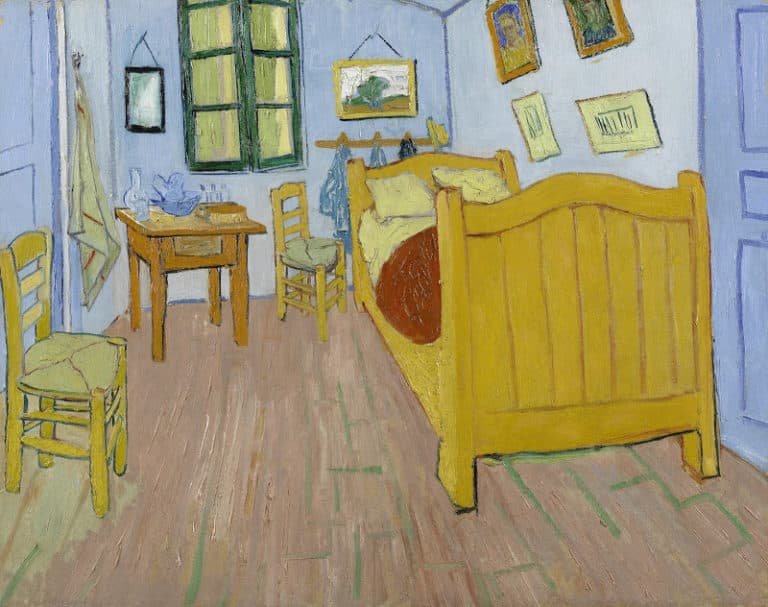

7. Vincent Van Gogh, The Bedroom (1888)

After two years in Paris, Vincent van Gogh settled in Arles from February 1888 to May 1889. There, he produced around 200 paintings, mostly inspired by the bright colour planes and sharp contours of Japanese prints. He created the Bedroom after a period of depression, saying it was to be “suggestive […] of rest or of sleep in general”, and that the painting had to “rest the head or, rather, the imagination” (letter to Theo van Gogh, 16 October 1888).

The room’s decoration is very simple. Apart from to the furniture, which simply consist of a bed and two chairs, the composition brings together simple objects, associated with relaxation. As such, we can spot a towel, a mirror, a pitcher witha glass, a basin with soap, a brush, as well as some quickly sketched flasks. On the walls hang some of Vincent’s paintings, including two portraits of his friends: painter Eugène Bloch on the left, soldier Paul-Eugène Milliet on the right. Although the perspective is obviously unstable, it is interesting to point out that the Yellow House, where Vincent van Gogh dreamed of founding a artists’ colony, was in fact a lop-sided building with asymmetrical corners.

The artist invites into the intimacy of his peaceful haven. He offers no projection onto the outdoors as the shutters are closed. He wished to convey expression through his choice of colours, evidence has shown that these have changed quite significantly since the painting was first made, due to the pigments’ aging. For instance, in letter from October 1888, the painter described lilac walls. Lastly, the Bedroom in Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum is the first of three versions Vincent van Gogh created of this painting – so you know what to do if you want to play spot the differences!

8. Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure (1905)

Unlike Vincent van Gogh, the windows are widen open here. Henri Matisse shows us the view from his studio on the Port d’Avall in Collioure. It was in this small fishermen’s village near Perpignan that Matisse first had the revelation of colour that initiated Fauvism. Open window, Collioure was one of the canvases on display in the (in)famous room n°VII of the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Art critic Camille Mauclair likened the bright colours of these paintings to having “a pot of paint flung in the face of the public”.

In this pivotal artwork, the composition is arranged around a succession of frames: the wall contains a French window, which opens onto a balcony (or a simple window ledge?), which in turn crops the landscape. But whilst we would expect the Southern light to generate strong shadows indoors, the colours remain bright everywhere. Working without shadows was one of the pictorial choices made by Matisse and his companion Derain in the summer of 1905.

The flat planes of green, red, pink and purple inside the room contrast with the small, divided, comma-shaped brushstrokes he uses for the foliage escaping from the flower pots to surround the frame in the middle-ground. The sketchy rendering of the boats, sea and the sky ultimately combines this rhythmic variety of the brushwork. In the history of painting, windows are a staple in terms of subject matter – Leon Battista Alberti, in the Renaissance, referred to painting to being an “open window” onto the world. But Matisse made this work into a manifesto of modern painting. Working from the feelings the landscape conjured up in him, he produced a visual system no longer merely descriptive, but purely decorative.

9. Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Morning (1950)

What makes this viewpoint by American painter Edward Hopper so original is that it shows us a character indoors… seen from the outdoors! In this piece from 1950, a woman leans forward onto a piece of furniture – most likely. She gazes intently into the distance, out of her bow window.

As was the case with Caspar David Friedrich, the model is probably based on Josephine Hopper, whom the painter married in 1924. The couple went to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, or the first time in 1930, before building a house there. Edward Hopper spent almost forty summers there. But despite the beauty of the surrounding landscapes, the painter does not show them to us here. The view the model is staring at remains a mystery to us.

In an almost photographic composition, the picture is divided in two, creating a visual tension between the indoor and the outdoor space. This is further highlighted by the abrupt shadows due to the morning light. Hopper also simplified the house into geometric shapes, thereby compressing the pictorial space. The house’s austerity contrasts with the vast, wild garden. What’s more, the viewer, the model and the landscape are all isolated from each other. The glass distances us from the wistful woman, who in turn seems disconnected from the compelling view. Although the scene looks mundane at first glance, and lacks any narrative, the artist creates a silent yet evocative atmosphere.

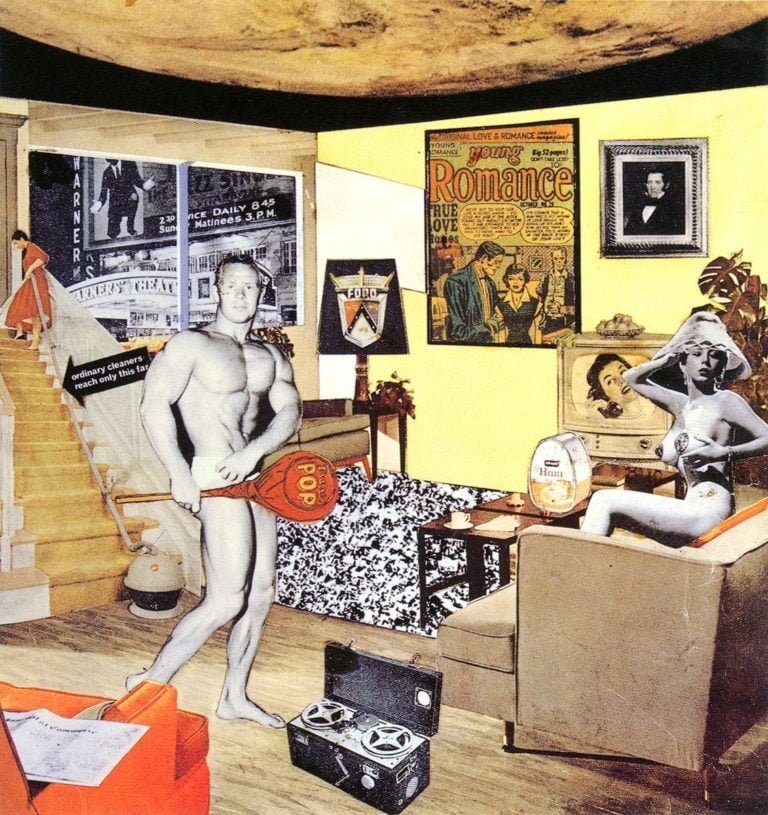

10. Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? (1956)

This collage was initially created by British artist Richard Hamilton as a poster for the This is Tomorrow exhibition in 1956, for which he also designed an installation. But don’t be fooled by its small format: this major work was probably the first piece of Pop Art. Made by assembling magazine cut-outs, the artwork was a parody of USA advertising culture in the 1950s. As for the title, it was directly copied from an issue of Ladies ’Home Journal.

Hamilton’s interior is eye-catching to say the least. It is filled with all the most fashionable and desirable objects of the time: the television, the Hoover vacuum cleaner with its extra-long hose, the record player, or the lampshade bearing Ford crest. The composition is extremely busy and constantly stimulates the gaze. In the 1950s, manufactured goods were indeed flooding into the United Kingdom, courtesy of the newly prosperous American economy.

But Hamilton is by no means acclaiming this consumerism. The apartment’s owners of this, albeit glamorous, could also be perceived as vulgar. The man of the house, with his exacerbated muscles and his vacant gaze, holds a lollipop-dumbbell with the word “POP” – for Pop Art. He seems to be pointing towards his partner, who is lying on the sofa. In this Cold War context, the ceiling, on the other hand, most likely evokes the Space Race. This interior brilliantly captures the spirit of its time, both fascinating the artist – who seems to have discreetly signed with the tinned ham (for “Hamilton”) and left him skeptical.

This is absolutely amazing and so wonderful to have access to this via my iPhone ! I am stranded in Tunisia with my daughter . Thank you very much Charlotte for enabling us to have some rich reading and see such beautiful works of art.. It helps wind away the hours of our confinement here in Zarzis. X

Hi Sandie, thank-you for your comment. I am so pleased you enjoyed the blog post and that it was a welcome distraction 🙂 Wishing you and your daughter all the best xx

Joni sent me your blog. Thank you for introducing me to new paintings and pointing out things I hadn’t noticed or didn’t know about old favourites. Your colours are much brighter/better than my little reproduction of the Hopper; I like it better now!

Glenis