In 2020, face masks are everywhere and have very much become a part of our daily lives. Part of the reason why they are so disconcerting is because they conceal part of the face, which is the main vehicle for our emotions. This in turn leads us to question our own identity. Through ten examples, let us examine some of the various uses and meanings linked to masks in Art History.

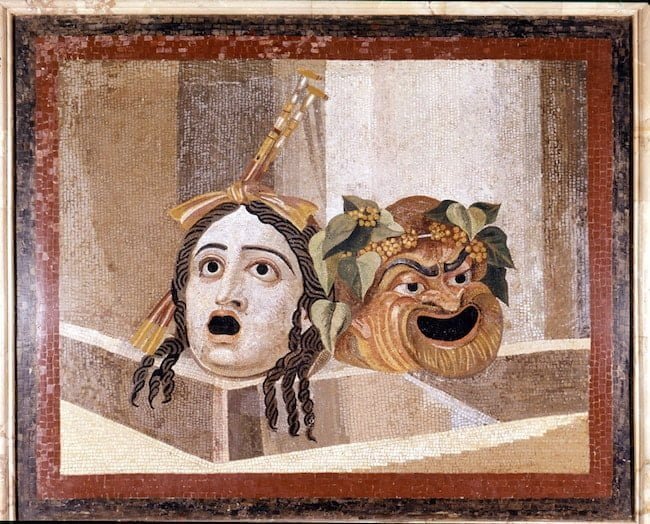

1. Stereotyped theatrical masks: Roman mosaic with stage masks, 2nd century AD.

Masks have been present in art history since Antiquity, and one of their first functions was linked to cross-dressing in the performing arts. This Roman mosaic, found in 1824 on Mount Aventine, shows a familiar image. It recalls what known today as the symbol of theater today: a laughing mask – depicting the art of Comedy – and a grimacing mask for Tragedy.

But on closer inspection, the iconography is different here. These two masks actually evoke a form of comedy. On the left, a young woman seems overwhelmed by her misfortunes, while the male character on the right, with his extravagant expression, seems to be laughing at her expense. The vine leaves on his head evoke the god Dionysus – often associated with theatrical arts. The stereotypical nature of these characters is typical of the New Comedy, a Greek drama genre which appeared in the 4th century BC and developed throughout the Roman Empire.

Although these masks recall human emotions, they are both exaggerated and fixed. The mask supports the actors’ dramatic skills while narrowing it, since do not allow for variety of expressions. Actors therefore remain in the specific role suggested by the playwright. The mosaic artist’s delicate rendering of perspective is a reminder that these masks, placed against two walls, are facsimiles of faces. Just like the two flutes placed behind them, they are inded inanimate accessories, but are essential to the structure of classical drama.

2. Magical funerary masks: Mask of Malinaltepec, Teotihuacan , 300-500 and 900-1521 AD.

In some civilizations, masks have a magical dimension. This famous stone mask discovered in Malinaltepec, in southwestern Mexico, is one such example. Research in 2008 confirmed its authenticity, which had been questioned since its discovery in 1921. It dates from the peak of the city of Teotihuacán, between 300 and 500 AD.

3. Mysterious masks: Lorenzo Lippi, Allegory of simulation, ca 1640

In this painting by Lorenzo Lippi, called Woman with a Mask for a long time, the mask is subject to different interpretations. The sole presence of the mask in the painting could have made it possible to identify the young woman as Thalia or Melpomene, the muses of Comedy and Tragedy. But in addition to the mask, whose expression is mostly hidden, the female character woman holds a pomegranate in her left hand. This unusual combination makes the iconography more complex.

Lippi, who was also a poet, frequented the literary circles in Florence, so it makes sense to look at a symbolic interpretation of the painting. Since it is made up of a multitude of small seeds, the pomegranate has often served as a symbol of unity in Christian art. But in Greek mythology, it is also the fruit offered by Hades, the god of the underworld, to Persephone, thereby condemning her to reside with him: she had eaten food belonging to the realm of the dead.

What conclusions can we reach, then? the mysterious air of the young woman does not help us much. Could she be an actress or simply someone who habitually takes on different roles? Now called Allegory of Simulation by the museum in Angers, the painting might refer to the masks we all wear in social contexts, and which are sometimes used to deceive others? In any case, the painting invites us to be wary of appearances.

4. Medical masks: Paul Fürst, Doktor Schnabel in Rom (Doctor Beak in Rome), ca 1656.

However ridiculous this outfit may seem to us today, it represents the actual clothing worn by the doctors who treated victims of the bubonic plague in the 17th century. This German engraving represents one of the plague doctors hired by the city of Rome during the epidemic that shook Italy in 1656-1657.

This invention of French doctor Charles Delorme in 1619 was designed to protect these doctors against putrid odors. Indeed, the now obsolete miasma theory asserted that the contamination was caused by toxic air. The notorious beak shaped mask covered the whole head and was filled with dried herbs and flowers, which were thought at the time to purify the air. The integrated glasses allowed the doctor to see .

The effeciency of this costume was far from spectacular, as was the bloodletting and leech cure. But in addition to the mask, the plague doctors wore gloves, a hat, as well as a stick that allowed them to examine people without touching them, while respecting physical distancing… Finally, their long waxed leather coat, which was meant to prevent miasma from clinging to it, in fact protected them against fleas – the real culprits of the bubonic plague bacteria.

5. Embodied theatrical masks: « Hannya » Noh Mask, Japan, 1650-1750.

Imagine a mask being more alive than an actual a human face? Fixed in its present form around 1400, Japanese Noh is one of the most sophisticated forms of mask art in Asia. Constructed around songs and dances, Noh theater creates a stage that allows spirits to come and tell stories to the living who attend the show.

Unlike other forms of drama, all the actors wear masks, the dimensions of which are somewhat smaller than their faces. While these filter their voices and reduce their field of vision, Noh masks are considered more expressive than a human face, as they stimulate the viewer’s imagination, thereby surpassing and transcending “superficial” human emotions.

They can embody five main categories of characters: deities, men, women, lost spirits (the Hannya mask opposite represents the specter of a demented and jealous woman seeking revenge in the world of the living) and finally demons. As such, the masks are carefully preserved by the actors who, before going on stage, invest them as a sacred object, charged with the presence of their character but also that of the actors who wore the mask before them.

6. Masks of deceit: Claude Gillot, Le Tombeau de Maître André, 1716-1717

The commedia dell’arte appeared in Italy around the 16th century. Wandering troupes of ten to twenty actors would perform in public , improvising comic sketches based mainly on romantic intrigues. The gestural essence of commedia dell’arte, as well as their colourful repertoire of fixed characters, contributed to the influence and popularity of this form of amusement in the Fine Arts.

The painter Claude Gillot (1673-1722), unfairly overshadowed by his pupil Watteau, produced many paintings on this theme. Le Tombeau de Maître André illustrates the first scene of an Italian farce by Brugière de Barante, performed for the first time at the Comédie-Italienne in 1695, and itself inspired by the fable “The Oyster and the Pleaders” by Jean de La Fontaine. The clear contrast between the wooden planks on the ground and the landscape in the background makes it clear that this is actually a stage backdrop and we are looking at a theatrical scene.

The painting depicts a quarrel between Mezzetin the schemer (left) and Scaramouche the gloater (right), who are arguing over a bottle of wine. The candid character Pierrot is also there, wearing his iconic white outfit. He expresses surprise at the ironic outcome of the dispute. Harlequin, who was called to the rescue to act as referee, puts an end to the argument by drinking he coveted wine himself! The mask worn here by Harlequin therefore evokes the character’s unpredictability and deceitfulness.

7. Haunting masks: Arnold Böcklin, Shield with the face of Medusa, 1897

The frightening Medusa, the Gorgon who turned anyone who met her gaze to stone, became a favoured motif in art from the 5th century BC, if only for ornamental purposes. But did you know that before she became a dreaded famous snake-haired figure, Medusa was priestess in the temple of Athena? The goddess, who was jealous of her beauty, transformed her into a snake-haired monster to punish her (!) for having been raped by Poseidon, the god of the seas, .

Roman poet Ovid recounts, in his Metamorphoses, that Perseus managed to kill Medusa by reflecting her gaze back at her thanks the reflection on his polished brass shield. After severing her head, the hero placed it on his shield. This precious weapon notably enabled him to transform King Atlas into a mountain for being unhospitable to him… Medusa therefore acquired a highly protective power, which repelled danger.

In 1885, archaeologist Georg Treu organised an exhibition in Berlin combining ancient objects and contemporary works. On this occasion, Arnold Böcklin, who was passionate about Greek and Roman Antiquity, designed an initial version of this painted papier-mâché shield decorated with a Medusa mask. With this piece, the Swiss Symbolist painter places the viewer in a disturbing face to face with Medusa.

We are invited to look the Gorgon straight in the eye despite the danger this entails… And as she stares back at us, we contemplate her death, since the expression on her face is the one she has as she drew her last breath, since she petrified herself. This mask could therefore be understood as a confrontation with death: that of Medusa, but also ours seen by Medusa.

8. Masks as social commentary: James Ensor, Ensor with masks, 1899

Masks appear both recurrently and uniquely in the work James Ensor (1860-1949). He was probably inspired by the souvenir and curiosity shop owned by his family in Ostend. The boutique sold miniature boats, seashells, old books, engravings, china, as well as carnival masks. Carnival also marked the beginning of the summer season for this Flemish seaside resort, which gained in popularity when King Leopold I decided to establish his summer residence there.

In 1899, James Ensor produced this self-portrait which depicts him surrounded by all sorts of masks, which seem to encompass Asian, commedia dell’arte and animal masks… No bodies can be seen within the density of the crowd, but there is a striking contrast between the painter’s gaze and the ghostly mass of hollow eyes. But beyond the anguish this image generates, further emphasised by the presence of a few skulls, the masks take on a social critique role here.

The painting conveys a feeling of isolation, which is typical of this non-conformist artist. Ensor was misunderstood by his teachers at the Academy of Brussels, then by art critics. Frustrated by the lack of recognition from his peers, he introduced grimacing masks into his art from 1883 to denounce the hypocrisy of the bourgeois society of his time. This portrait shows a lonely James Ensor, surrounded but lucid, by the great farce of human comedy … a masquerade in a very litteral sense.

9. Geometric Masks: Man Ray, Black and White, 1926

The popularity of African masks in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century is well documented. The famous surrealist photographer Emmanuel Radinsky, or Man Ray (1890-1976), was no exception to the rule. Originally from a Jewish Russian family that emigrated to the United States, he met Marcel Duchamp in 1915, before settling in Paris in 1921. There he met Alice Prin, better known as Kiki de Montparnasse, and had a fiery romance with the one who was both his model and his muse.

In 1926, this portrait photograph was published in French Vogue under the title Face of Mother of Pearl and Mask of Ebony. The image is full of contrasts. Kiki de Montparnasse’s face is lays on the table, giving her an almost ornamental status, as she holds a Baoulé mask from Ivory Coast vertically. The face and the mask are distinct in nature (living vs. inanimate) and their inverted shades of grey. While the dark shadows indicate the hollow areas on the model’s fair skin, the white reflections highlight the protruding areas on the surface of the mask.

However, the face and the mask have a lot more in common than one might think. The bright light used by Man Ray creates crisp drop shadows. The oval shape of Kiki de Montparnasse’s face echoes the geometry of the mask, while her precise, linear makeup, typical of the 1920s, stylises her features by stretching her eyes and shrinking her mouth… Perhaps this visual comparison could to be interpreted as a commentary on visual identity as a chosen construct. After all, what if Kiki de Montparnasse were ultimately just a fashionable alter ego mask worn by Alice Prin?

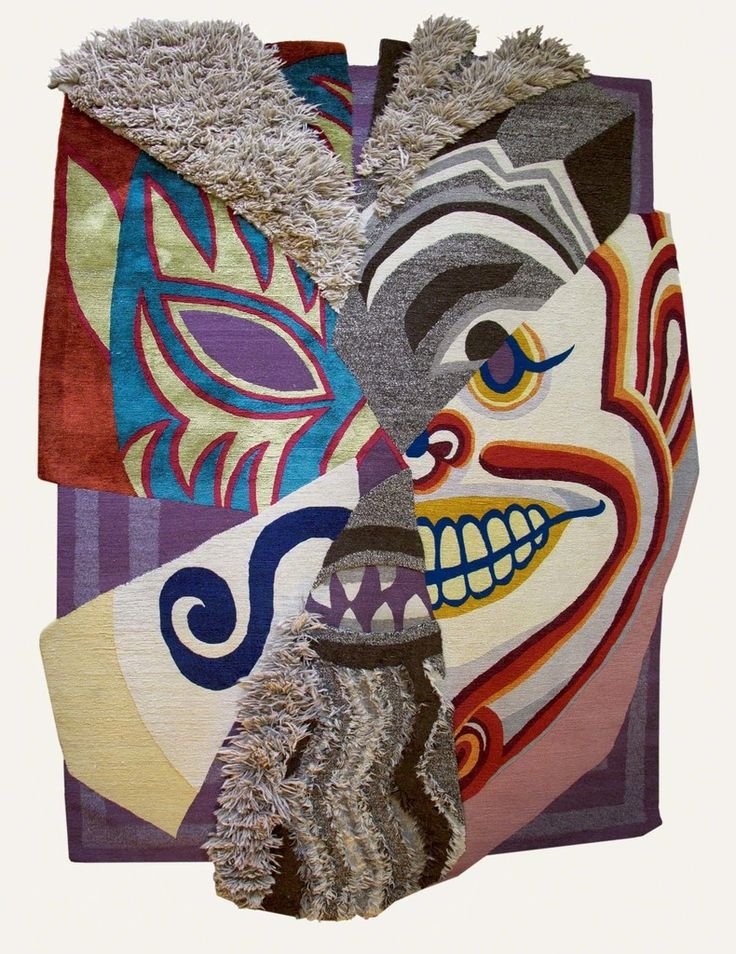

10. Globalised maks: Christoph Hefti, World Mask, 2014

Masks have been explored under many different aspects throughout the history of art, according to times and civilisations, and this selection addresses only a few. One of the trends in contemporary art is to summarise topics in the light of art history and this also applies to the iconography of the mask. Alongside his career in fashion, Swiss textile designer Christoph Hefti is working as a visual artist. His World Mask, produced in 2014, was recently exhibited at the Aargauer Kunsthaus, as part of the exhibition “MASK in present-day art”.

Deeply drawn to traditional skills, the artist traveled to Nepal. This was there that he had this World Mask – actually a wool and silk rug – hand-knotted using a traditional local technique. Christoph Hefti introduces a reflection on the roles of “creator” (the one who comes up with the idea) and of the “craftsman” (who carries it out). This division is common in the field of applied arts, bu much less obvious among visual artists.

Hung vertically, the piece creates a hybrid figure made up of different masks forming a single face. Clockwise from the upper right corner, we can identify a fragment of a ritual African mask, a Tibetan spiritual protection mask , a carnival mask from Guatemala and a Mexican combat mask . In the globalized context we live in today, the various roles of the mask come together, highlighting both the specificities of each culture and giving them a common form of expression.

Excellent review. Merci bien!!!